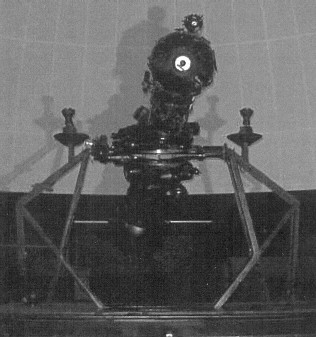

These photographs show the two earliest versions of the Zeiss Planetarium Projector. The first image shows the very first projector, the Zeiss Mark I, which was introduced at the Deutsches Museum in Munich 100 years ago today. The second image, the Zeiss Mark II, operated in the original Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science in Pittsburgh from 1939 to 1991 and was the first planetarium projector placed on an elevator.

(Image Sources --- Zeiss Mark I: Wikipedia.org; Zeiss Mark II: History of Buhl Planetarium Internet Web-site)

By Glenn A. Walsh

Reporting for SpaceWatchtower

Today (2023 October 21) marks the centennial of the planetarium projector, which made its debut at the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany on 1923 October 21. This means of displaying the motions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars of the sky, without any concern for inclement weather, quickly developed in cities around the world.

The concept of a projection planetarium was first conceived on 1914 February 24 at a meeting of staff scientists of the Carl Zeiss Company in Jena, Germany. Due to delays caused by the First World War, the first actual planetarium projector would not be produced until nearly a decade later.

The idea came as a solution to a problem brought on by a request from a client, Oskar von Miller. Mr. von Miller, a well-known German engineer, had spearheaded the establishment of the first modern-type science and technology museum, the Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany, which opened to the public on 1906 November 12. In 1913, German Astronomer Max Wolf, former Director of the Baden Observatory in Heidelberg, urged Mr. von Miller to include, in the Deutsches Museum, a way to realistically reproduce the night sky, in detail, including the motions of the planets.

Also in 1913 (before Chicago's Adler Planetarium opened in 1930), a large-scale, mechanical celestial sphere, called the Atwood Sphere, opened to the public in the Museum of the Chicago Academy of Sciences (today, it is displayed in the Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum). In a mechanical celestial sphere, a small number of people would enter an enclosure where light from outside the enclosure would twinkle through small holes in the sphere, as a display of stars that could be seen outdoors; additionally, the sphere would spin around the viewers demonstrating star movement. The concept of a mechanical celestial sphere, large enough to accommodate at least ten people, dates back to 1664 when the Globe of Gottorf was installed in the Kunstkammer Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Mr. von Miller wanted a mechanical celestial sphere for the Deutsches Museum. However, he asked that the Carl Zeiss scientists find a way to also display the movements of the Sun, Moon, and planets in the celestial sphere, something that was not included in previous spheres.

Two Carl Zeiss scientists, Walther Bauersfeld and Rudolf Straubel, offered an alternative on 1914 February 24: replace the small celestial sphere with a giant hemispheric dome, and use a bright central lamp to project the planets and stars onto the dome-sky.

In addition to being the first concept for a projection planetarium, it was also the first concept of a true, large-scale planetarium. Except for a small-scale Orrery, the previous celestial spheres had no way to demonstrate the motions of the planets.

A very primitive projection planetarium had been invented in 1912 by Professor E. Hindermann in Basel, Switzerland. Called an Orbitoscope, this spring-driven instrument included only two planets orbiting a Sun. A small light bulb on one planet projected shadows on the other two objects, accurately displaying retrograde loops and speed changes, but not much else.

Well after the end of World War I, the Carl Zeiss Company first demonstrated a large-scale projection planetarium in August of 1923, in a 16-meter dome set-up on the company's factory roof in Jena. The Zeiss Model I, known as the “Wonder of Jena,” was then dismantled and shipped to the Deutsches Museum.

On 1923 October 21, Mr. Bauersfeld, the Carl Zeiss Company Chief Design Engineer, demonstrated the Zeiss I in a program for invited guests at the Deutsches Museum. As the first public planetarium show, the professional and public reaction was enthusiastic. The planetarium projector was then returned to the Jena factory for finishing touches, and then permanently installed in the Munich museum on 1925 May 7.

This new educational tool greatly impressed scientists and civic leaders in Germany, resulting in six other German cities receiving Zeiss planetarium projectors by the end of 1926. By 1930, five more German cities had projectors. A much improved Zeiss Model II soon superseded the Zeiss I.

In 1927, the first Zeiss projector outside of Germany was installed in Vienna, and then a projector was installed in Rome in 1928 and one in Moscow in 1929. Other European cities to receive planetarium projectors from the Carl Zeiss Company, prior to World War II, included Stockholm (1930), Milan (1930), and Paris (1937). The first Asian planetarium projectors appeared in Osaka in 1937 and Tokyo in 1938.

Five Zeiss planetarium projectors were installed in America prior to World War II. The first came to the new Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum in Chicago in 1930. Founded by Chicago business leader Max Adler, the institution is part of Chicago's Museum Campus, which includes the Field Natural History Museum and the Shedd Aquarium. A visit in 1930 by Amateur Astronomers Association of Pittsburgh co-founder Leo Scanlon, and other members of the club, inspired the club to lobby for a planetarium to be built in Pittsburgh.

During a Web Seminar on 2020 September 3, Mike Smail, Director of Theaters and Digital Experience at the Adler Planetarium, announced that America's oldest planetarium projector had been found in storage in central Ohio and recovered. The author, Glenn A. Walsh, is proud to have assisted in the resolution regarding the mystery of what had been a missing historic projector.

The second U.S. planetarium, the Fels Planetarium, was installed as part of Philadelphia's Franklin Institute in 1933; the planetarium opened two months before the Franklin Institute Science Museum was completed in 1934. It is said that Samuel S. Fels, the soap company president and philanthropist who funded the planetarium, missed the debut performance in Fels Planetarium. He was late and refused to be seated late, as he felt nothing should interrupt a planetarium show once it has begun!

Two American planetaria opened in 1935. On May 14, Griffith Observatory and Planetarium opened in Griffith Park in Los Angeles. While the large planetarium dome is in the center of the facility, two smaller observatory domes are on the east and west sides of the building. The east dome houses a 12-inch Zeiss refractor telescope, one of the earliest public observatories; solar telescopes are housed in the west dome, with a coelostat which sends the images to the public exhibit gallery. Located on a high hill just above Hollywood, Griffith Observatory has been included in numerous motion pictures (including James Dean's Rebel Without a Cause) and television programs (including Star Trek: Voyager).

Hayden Planetarium opened in New York City's long-established American Museum of Natural History on 1935 October 3. After a very controversial renovation, which included the demolition of the original Hayden Planetarium building, the new Hayden Planetarium opened as part of the much larger and more impressive Rose Center for Earth and Space in 2000. Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, nationally known as a host of PBS science programs, is the long-time Director of the Hayden Planetarium.

Also in 1935, the Buhl Foundation committed to building a planetarium in Pittsburgh, in memory of department store co-founder Henry Buhl, Jr. Opened in 1939, Pittsburgh's original Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science included five public galleries of exhibits of the physical sciences, and even one life science presentation. A public observatory, with a rather unique 10-inch Siderostat-type refractor telescope, was added in 1941.

Buhl Planetarium's Zeiss II Planetarium Projector was the first planetarium projector to be placed on an elevator (a special worm-gear elevator custom-built by the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company), and the Theater of the Stars was the first planetarium theater to include a permanent theatrical stage and a special sound system for the hearing-impaired. Buhl used their Zeiss II, with no major modifications, until the building closed as a public museum in 1991. The Zeiss II is now on public exhibit, but not in use, in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Science Center, where the Henry Buhl, Jr. Planetarium and Observatory now utilizes a full-dome, digital projection system.

Two American-built star projectors are of special note. In 1937, the Korkosz brothers installed a projector, which projects 9,500 stars but no planets, in the Springfield Museum of Science in Springfield, Massachusetts. Including a major restoration in 1996, the staff of the Springfield Museum of Science have lovingly maintained this historic projector, which continues providing astronomy education to young and old alike, to this day!

After World War II, neither Zeiss factory in war-torn Germany was capable of producing planetarium projectors for several years. Thus, the California Academy of Sciences decided to build a one-of-a-kind planetarium projector for the Morrison Planetarium in San Francisco, which opened in 1952. Today, Morrison Planetarium claims to have one of the world's largest all-digital planetarium theaters.

With the post-war boom in America, many new educational facilities were constructed in the second half of the 20th century, including new planetaria, science museums, and public libraries. New technology has changed the planetarium experience and increased the educational capabilities of planetaria. Likewise, planetarium-type computer programs have brought the planetarium experience to school and home computers, and even to hand-held smart telephones.

Internet Links to Additional Information ---

Planetarium: Link >>> https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planetarium

Centennial of the Planetarium (International Planetarium Society):

Link >>> https://planetarium100.org/

Related Blog-Posts ---

"Mystery Solved! Oldest U.S. Planetarium Projector Found & Recovered." Fri, 2020 Sept. 18.

"100 Years Ago: Planetarium Concept Born." Mon., 2014 Feb. 24.

Source: Glenn A. Walsh Reporting for SpaceWatchtower, a project of Friends of the Zeiss

© Copyright 2023 Glenn A. Walsh, All Rights Reserved

Saturday, 2023 October 21

Like This Post? Please Share!

More Astronomy & Science News - SpaceWatchtower Twitter Feed:

Link >>> https://twitter.com/spacewatchtower

Astronomy & Science Links: Link >>> http://buhlplanetarium.tripod.com/#sciencelinks

Want to receive SpaceWatchtower blog posts in your in-box ?

Send request to < spacewatchtower@planetarium.cc >.

gaw

Glenn A. Walsh, Informal Science Educator & Communicator (For more than 50 years! - Since Monday Morning, 1972 June 12):

Link >>> http://buhlplanetarium2.tripod.com/weblog/spacewatchtower/gaw/

Electronic Mail: < gawalsh@planetarium.cc >

Project Director, Friends of the Zeiss: Link >>> http://buhlplanetarium.tripod.com/fotz/

SpaceWatchtower Editor / Author: Link >>> http://spacewatchtower.blogspot.com/

Formerly Astronomical Observatory Coordinator & Planetarium Lecturer, original Buhl Planetarium & Institute of Popular Science (a.k.a. Buhl Science Center), America's fifth major planetarium and Pittsburgh's science & technology museum from 1939 to 1991.

Formerly Trustee, Andrew Carnegie Free Library and Music Hall, Pittsburgh suburb of Carnegie, Pennsylvania, the fourth of only five libraries where both construction and endowment funded by famous industrialist & philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.

Author of History Web Sites on the Internet --

* Buhl Planetarium, Pittsburgh: Link >>> http://www.planetarium.cc Buhl Observatory: Link >>> http://spacewatchtower.blogspot.com/2016/11/75th-anniversary-americas-5th-public.html

* Adler Planetarium, Chicago: Link >>> http://adlerplanetarium.tripod.com

* Astronomer, Educator, Optician John A. Brashear: Link >>> http://johnbrashear.tripod.com

* Andrew Carnegie & Carnegie Libraries: Link >>> http://www.andrewcarnegie.cc

* Other Walsh-Authored Blog & Web-Sites: Link >>> https://buhlplanetarium.tripod.com/gawweb.html

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete