This is the last image of Jupiter taken by NASA's Juno spacecraft, as it approached Jupiter on 2016 June 29, at a distance of 3.3 million miles / 5.3 million kilometers from the Solar System's largest planet. After this photograph was taken, Juno's science .instruments were powered-down as it prepared for the difficult orbit insertion maneuver.

(Image Sources: NASA / JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS)

By Glenn A. Walsh

Reporting for SpaceWatchtower

Late evening on American Independence

Day (2016 July 4), and just one second difference from pre-burn

predictions, NASA's Juno space probe entered polar orbit of the Solar

System's largest planet, Jupiter.

The precarious orbit insertion maneuver

occurred at the scheduled time of 11:05 p.m. Eastern Daylight Saving

Time (EDT) / July 5 at 3:05 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).

However, NASA officials and scientists did not know the maneuver was

successful until 11:53 p.m. / July 5 at 3:53 UTC, 48 minutes later,

as the orbit insertion was accomplished by Juno's auto-pilot. This is

because Jupiter is currently 48 light-minutes from Earth, and radio

signals take 48 minutes to travel between Jupiter and the Earth, at

this time.

Entering a highly elliptical orbit of

Jupiter, which lasts for 53 days, was difficult and dangerous, as

Juno had to risk Jupiter's heavy radiation belt, as well as debris

orbiting the planet. This particular orbit will allow Juno to avoid

Jupiter's dense radiation most of the time, but also make close

investigations of Jupiter's North and South Poles as well as the

Equator.

The spacecraft's nine science

instruments and camera were deactivated before attempting the orbit

insertion, to ensure that nothing interfered with the important

engine burn; so, there are no actual photographs of the maneuver.

However, the maneuver seemed to go flawlessly, when NASA's Jet

Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California received

confirmation that Juno had actually entered orbit around Jupiter. JPL

scientists worked along-side engineers from Lockheed Martin, the primary aerospace

contractor for the Juno mission.

Prior to turning-off the camera, Juno

took a time-lapse video of Jupiter and some of its moons, which NASA

released to the public. This video included the first mission

surprise: Jupiter's moon, Callisto, appeared dimmer than expected.

Juno will take further images of Callisto during the mission.

At a 1:00 a.m. EDT / 5:00 UTC, July 5,

NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory (California Institute of Technology)

media briefing, where questions were taken from both news reporters

and from the public via Social Media, Juno's principal science

investigator Scott Bolton announced, “NASA did it again,”

regarding the tricky space maneuver. He added, "The mission team

did great. The spacecraft did great. We are looking great. It's a

great day." Scott Bolton does space research at the Southwest

Research Institute in San Antonio.

Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager

from JPL agreed saying, "The spacecraft worked perfectly, which

is always nice when you're driving a vehicle with 1.7 billion miles

on the odometer. Jupiter orbit insertion was a big step and the most

challenging remaining in our mission plan, but there are others that

have to occur before we can give the science team members the mission

they are looking for."

Jupiter is one of four “gas giant”

planets in the Solar System (the others being Saturn, Uranus, and

Neptune), whose clouds are primarily composed of hydrogen and helium.

The inner planets, including Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, as well

as many objects in the Asteroid Belt and Kuiper Belt (including

Pluto) are rocky-type planets.

It is hypothesized that Jupiter formed

shortly after the formation of our Sun, and the gravity from

Jupiter's massive body may have led to the formation of the other

planets. By studying Jupiter, we may find clues to the formation of

the Earth.

Juno has a big mission for

investigating a big planet. The space probe's primary goal is to

understand the origin and evolution of Jupiter, using nine major

science instruments. During the mission, Juno will:

- More accurately measure Jupiter's gravity to try to determine if Jupiter has a solid planetary core, underneath the heavy cloud cover.

- Map Jupiter's intense magnetic field.

- Measure the amount of water and ammonia in the deep atmosphere, which could give a clue as to the planet's origin.

- Observe the planet's auroras.

- Study the cloud belts and the mysterious Red Spot, a huge cyclone larger than the Earth, that has existed for hundreds of years, but now seems to be shrinking in size.

- Use data accumulated to try to understand how giant planets form and their role in the organizing of the Solar System.

- As many planets being discovered around other stars are as large or larger than Jupiter, more information from Jupiter could help us understand solar systems around other stars.

In the beginning, Juno will complete

two 53-day orbits, each known as a “Perijove Pass.” Juno's

scientific instruments will be turned-back-on by August 27; this is when the first close-up pictures of Jupiter are expected. On

October 19, Juno's engines will change the spacecraft's orbit to a

much closer 14-day orbit, where it will stay until the end of the

mission in 2018, when it will have completed 37 orbits of Jupiter.

Juno will descend as close as 3,000

miles / 5,000 kilometers to the cloud-tops of Jupiter, the closest

any spacecraft has come to the planet. Juno's computer and

electronics are sealed in a titanium vault, to protect them from

Jupiter's massive radiation. However, Juno is still expected to

encounter radiation in excess of 10 million dental X-rays during the

mission. Hence, the space probe can only take so much radiation

before systems will begin to fail, and the mission is slated to end

before the radiation destroys the computer and electronics.

The Juno spacecraft was launched from

the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida on 2011 August 5.

However, it did not have enough fuel to go straight to Jupiter, which

is why the flight took nearly five years to travel 1.8 billion miles

/ 2.8 billion kilometers. Juno first went into an elliptical orbit of

the Sun.

In October of 2013, Juno passed by the

Earth for an Earth gravity-assist (a.k.a. “sling-shot” maneuver),

which gave the spacecraft the additional energy needed to reach

Jupiter. This gravity-assist gave Juno a boost of more than 8,800

miles-per-hour / 3.9 kilometers-per-second.

For the first time for a NASA mission

to the outer planets, the spacecraft is powered by solar energy,

rather than by a type of nuclear power (radioisotope thermoelectric

generator). Solar panels are normally used for powering Earth

satellites and space probes to the inner planets, which are much

closer to the Sun than Jupiter. Juno's three huge solar arrays will

not only provide energy, 500 watts, for powering the nine scientific

instruments, but they will also be key in stabilizing the spacecraft.

Juno is the second spacecraft to orbit

Jupiter. The space probe Galileo orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003.

Eventually, NASA allowed Galileo to burn-up in Jupiter's atmosphere,

to prevent it from inadvertently crashing onto one of Jupiter's

moons, and subsequently contaminating the moon with bacteria from

Earth. Likewise, at the end of Juno's 20-month, $1.1 billion mission,

it too will burn-up in Jupiter's atmosphere, for the same reason.

The European Space Agency (ESA) plans

to send a Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer space probe to the Jupiter system

in 2030, with a launch in 2022. This mission is the successor to the

originally proposed Jupiter Ganymede Orbiter by ESA.

NASA has also proposed an Europa

Multiple Fly-By Mission, which would be launched around 2022 and

include the fly-by of Jupiter's moon Europa 32 times while orbiting Jupiter, as well

as landing a spacecraft on this Galilean Moon.

Several more space probes have

investigated Jupiter, while flying-by and continuing into the outer

Solar System (except Ulysses). These included Pioneer 10 (1973),

Pioneer 11 (1974—on its way to Saturn), Voyager 1 (1979—on its

way to Saturn and Saturn's largest moon, Titan), Voyager 2 (1979—on

its way to Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune), Ulysses (1992—on its way

to a detailed study of the Sun), Cassini (2000—on its way to

Saturn), and New Horizons (2007—on its way to Pluto).

The spacecraft's name, Juno, comes from

the NASA acronym, JUpiter Near-polar Orbiter.

However, the name was also chosen because in Greco-Roman mythology,

the goddess Juno was the name of the wife of the god Jupiter. And,

Juno had the power to peer through clouds, created by Jupiter to hide

from his wife, and learn of her husband's mischief. Likewise, the

Juno spacecraft has the power to peer through the planet Jupiter's

dense clouds, to learn more of the secrets of our Solar System's

largest planet.

Internet Links to Additional Information ---

More about Juno:

Link 1 >>> https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/juno/main/index.html

Link 2 >>> https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juno_(spacecraft)

More about Jupiter: Link >>> https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter

More about robotic exploration of Jupiter:

Link >>> https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exploration_of_Jupiter

Social Media sites to follow the Juno mission:

Facebook - Link >>> http://www.facebook.com/NASAJuno

Twitter - Link >>> http://www.twitter.com/NASAJuno

Source:

Glenn A. Walsh Reporting for SpaceWatchtower, a project of Friends of

the Zeiss.

2016 July 5.

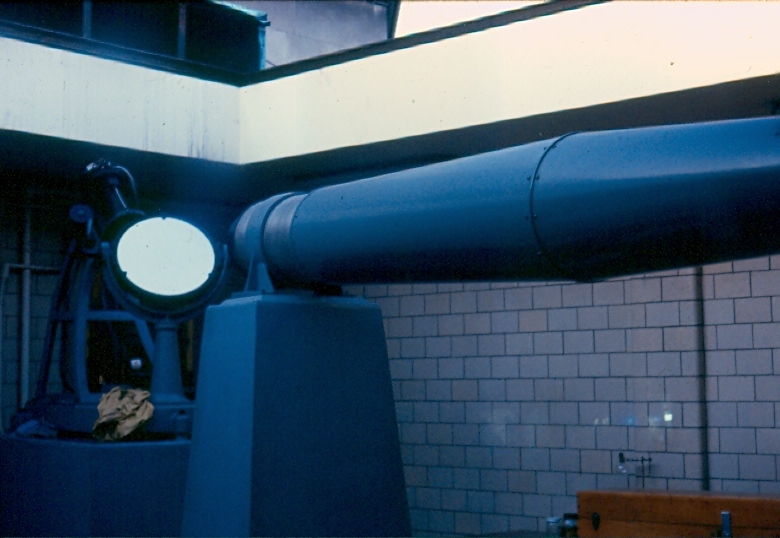

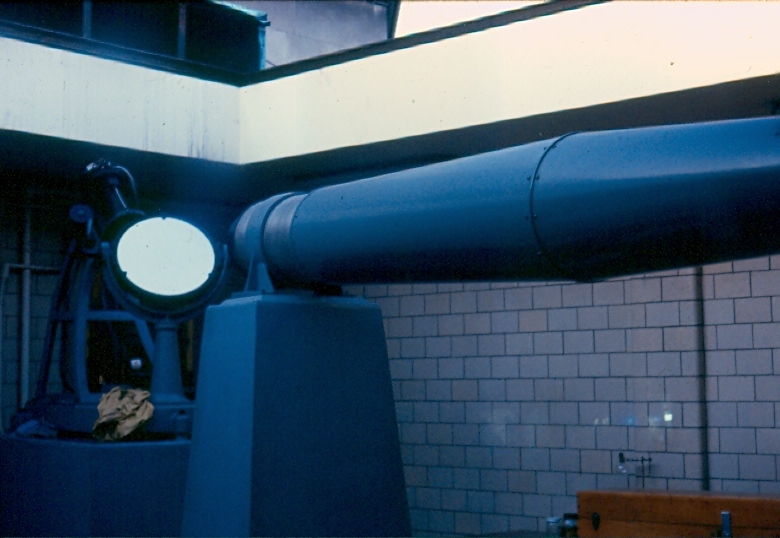

2016: 75th Year of Pittsburgh's Buhl Planetarium Observatory

Link >>> http://spacewatchtower.blogspot.com/2016/01/astronomical-calendar-2016-january.html

Like This Post? - Please Share!

Want to receive SpaceWatchtower blog posts in your inbox ?

Send request to < spacewatchtower@planetarium.cc >..

gaw

Glenn A. Walsh, Project Director,

Friends of the Zeiss < http://buhlplanetarium.tripod.com/fotz/ >

Electronic Mail - < gawalsh@planetarium.cc >

SpaceWatchtower Blog: < http://spacewatchtower.blogspot.com/ >

Also see: South Hills Backyard Astronomers Blog: < http://shbastronomers.blogspot.com/ >

Barnestormin: Writing, Essays, Pgh. News, & More: < http://www.barnestormin.blogspot.com/ >

About the SpaceWatchtower Editor / Author: < http://buhlplanetarium2.tripod.com/weblog/spacewatchtower/gaw/ >

SPACE & SCIENCE NEWS, ASTRONOMICAL CALENDAR:

< http://buhlplanetarium.tripod.

Twitter: < https://twitter.com/spacewatchtower >

Facebook: < http://www.facebook.com/pages/

Author of History Web Sites on the Internet --

* Buhl Planetarium, Pittsburgh:

< http://www.planetarium.

* Adler Planetarium, Chicago:

< http://adlerplanetarium.

* Astronomer, Educator, Optician John A. Brashear:

< http://johnbrashear.tripod.com >

* Andrew Carnegie & Carnegie Libraries:

< http://www.andrewcarnegie.

* Civil War Museum of Andrew Carnegie Free Library:

< http://garespypost.tripod.com >

* Duquesne Incline cable-car railway, Pittsburgh:

< http://inclinedplane.tripod.

* Public Transit:

< http://andrewcarnegie2.tripod.

2016: 75th Year of Pittsburgh's Buhl Planetarium Observatory

Link >>> http://spacewatchtower.blogspot.com/2016/01/astronomical-calendar-2016-january.html

Like This Post? - Please Share!

Want to receive SpaceWatchtower blog posts in your inbox ?

Send request to < spacewatchtower@planetarium.cc >..

gaw

Glenn A. Walsh, Project Director,

Friends of the Zeiss < http://buhlplanetarium.tripod.com/fotz/ >

Electronic Mail - < gawalsh@planetarium.cc >

SpaceWatchtower Blog: < http://spacewatchtower.blogspot.com/ >

Also see: South Hills Backyard Astronomers Blog: < http://shbastronomers.blogspot.com/ >

Barnestormin: Writing, Essays, Pgh. News, & More: < http://www.barnestormin.blogspot.com/ >

About the SpaceWatchtower Editor / Author: < http://buhlplanetarium2.tripod.com/weblog/spacewatchtower/gaw/ >

SPACE & SCIENCE NEWS, ASTRONOMICAL CALENDAR:

< http://buhlplanetarium.tripod.

Twitter: < https://twitter.com/spacewatchtower >

Facebook: < http://www.facebook.com/pages/

Author of History Web Sites on the Internet --

* Buhl Planetarium, Pittsburgh:

< http://www.planetarium.

* Adler Planetarium, Chicago:

< http://adlerplanetarium.

* Astronomer, Educator, Optician John A. Brashear:

< http://johnbrashear.tripod.com >

* Andrew Carnegie & Carnegie Libraries:

< http://www.andrewcarnegie.

* Civil War Museum of Andrew Carnegie Free Library:

< http://garespypost.tripod.com >

* Duquesne Incline cable-car railway, Pittsburgh:

< http://inclinedplane.tripod.

* Public Transit:

< http://andrewcarnegie2.tripod.

No comments:

Post a Comment